The maritime sector is the sixth-largest emitter in the world

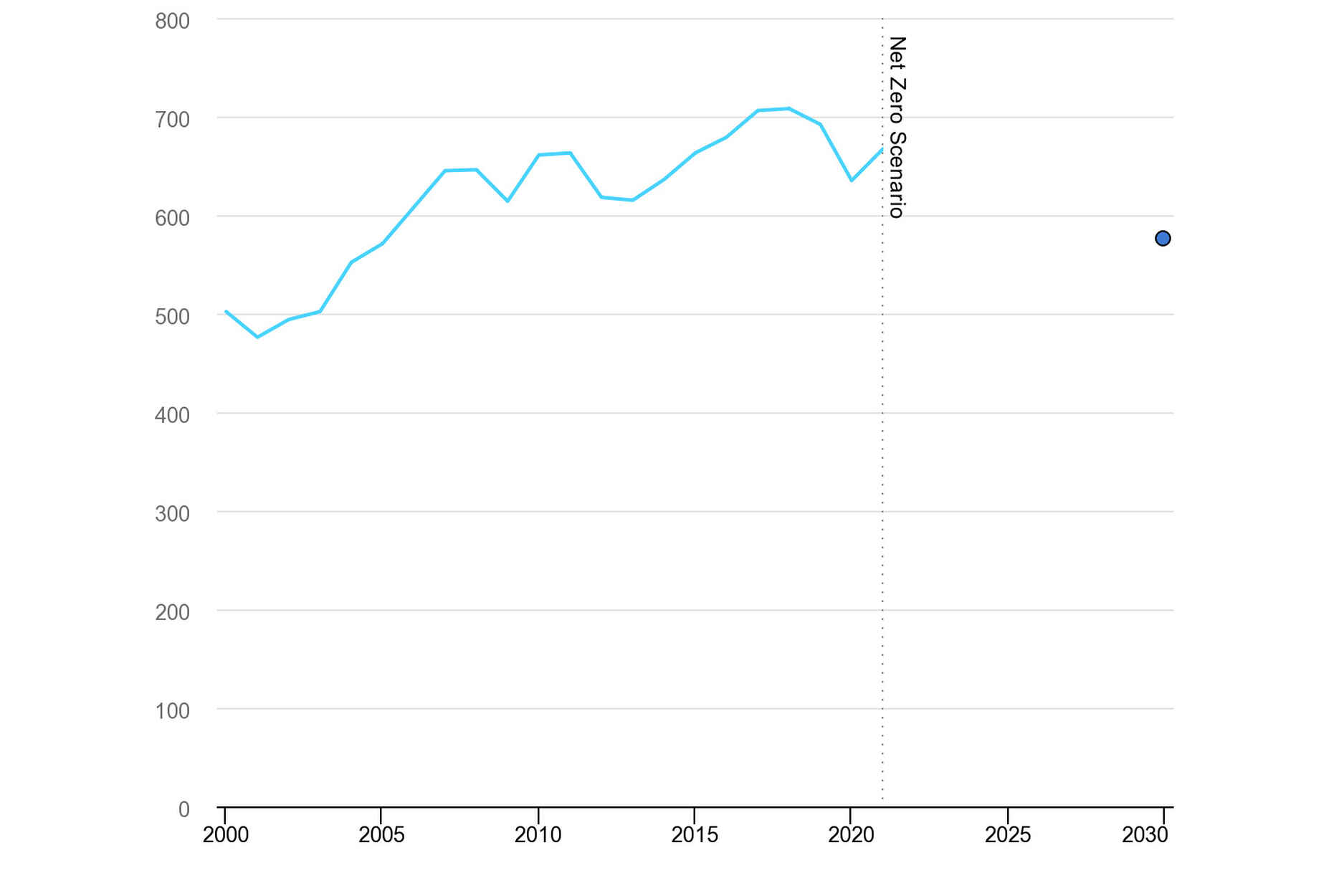

Shipping is a sector crucial for the world economies, as it is hauling goods of over USD 14 trillion, controlling 80% of global trade, and at the same time, it is the cheapest mode of transportation for goods worldwide.[1] Shipping is also responsible for around 2% of all emissions worldwide (Figure 1)[2], making the sector the sixth-largest emitter in the world after China, the U.S., India, Russia, and Japan. If no reduction policies and regulations are put in place, after a slight cut due to the pandemic, those emissions will inevitably keep on rising. Some projections show that emissions could increase by up to 130% of 2008 levels by 2050.[3] Moreover, a growing aspect of maritime is the tourism part i.e., cruisers. The global cruise market size was valued at USD 7.25 billion in 2021 and some estimations are that it will have a staggering growth in the years to come, expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.0% from 2022 to 2028[4]. At the EU level as well, maritime transport is a big polluter, representing 3% to 4% of the EU’s total CO2 emissions, or over 124 million tonnes of CO2 in 2021.[5]

Figure 1 - CO2 emissions from international shipping in the Net Zero Scenario, 2000-2030

Unlike the efforts in other sectors, such as power production, maritime is struggling to dent its emissions’ rise and decouple the growth the sector is experiencing (both cargo and passenger) from its emissions spike. The major issue with decarbonizing maritime is the lack of global concrete action of regulating emissions and setting reduction targets, as well as the difficulty to electrify it due to the nature of how ships and their engines are constructed. Some estimates put shipping at using more than 300 million tons of fossil fuels every year, roughly 5% of all global oil production. On the other hand, ocean-going container and cargo ships on intercontinental voyages are difficult to electrify because of the variability of conditions such undertaking would experience. There will be a necessity for a very, very, very big battery to cope with all the uncertainty, simply put, ships, especially those that sail through the oceans, cannot just add a battery in place of their fossil fuel engines.[6] Therefore shipping, along with aviation has remained outside the scope of electrification for the time being but is still in need of decarbonizing its energy consumption.

With the global push to halt the detrimental effects of climate change and rising temperatures, maritime is more and more in focus, with a renewed push to regulate emissions reductions in 2023. The International Maritime Organization (IMO), concluded on its last meeting on 7 July falling short of committing to full and rapid decarbonization, but with a last-minute agreement, that the world maritime sector will reach net zero emissions “close to 2050” with indicative checkpoint targets of “at least 20%, striving for 30%, by 2030” and “at least 70%, striving for 80%, by 2040”.[7] The targets however are not legally binding and remain out of line with the 1.5 C goal set with the Paris Agreement. The next push to set binding targets will be in 2027.

EU Maritime Decarbonization Quest

Despite the lack of global commitment to decarbonize maritime, there is a movement on a regional level, like in the European Union. The EU, as part of its 2050 net-zero target, has been more ambitious in setting emissions reduction and clean fuel targets for maritime, by introducing several new regulations, out of which three are quite important and will have long-term effects on the sector. One of the first measures targeting cleaner maritime fuels adopted under the new EU Fit-For-55 framework[8] is the 2% renewable fuels usage target for 2034, in case the Commission reports that in 2031 the renewable liquid and gaseous fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBO) amount to less than 1% in the fuel mix.

EU ETS

In Spring 2023, there was a major change to the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), when the maritime sector was incorporated into it. Unlike aviation, maritime was, up to that point, exempted from paying for its emissions. Why now? Due to the EU’s 2050 net-zero target but also due to the fact that maritime is responsible for 3% to 4% of the EU’s total CO2 emissions. Simply put, the sector responsible for around 75% of EU external trade volumes and 31% of EU internal trade volumes, making it an essential transportation system[9], must have a price tag on its emissions, as the fuels being used are almost entirely fossil fuel-based. This should further assist the maritime in its decarbonization pathways.

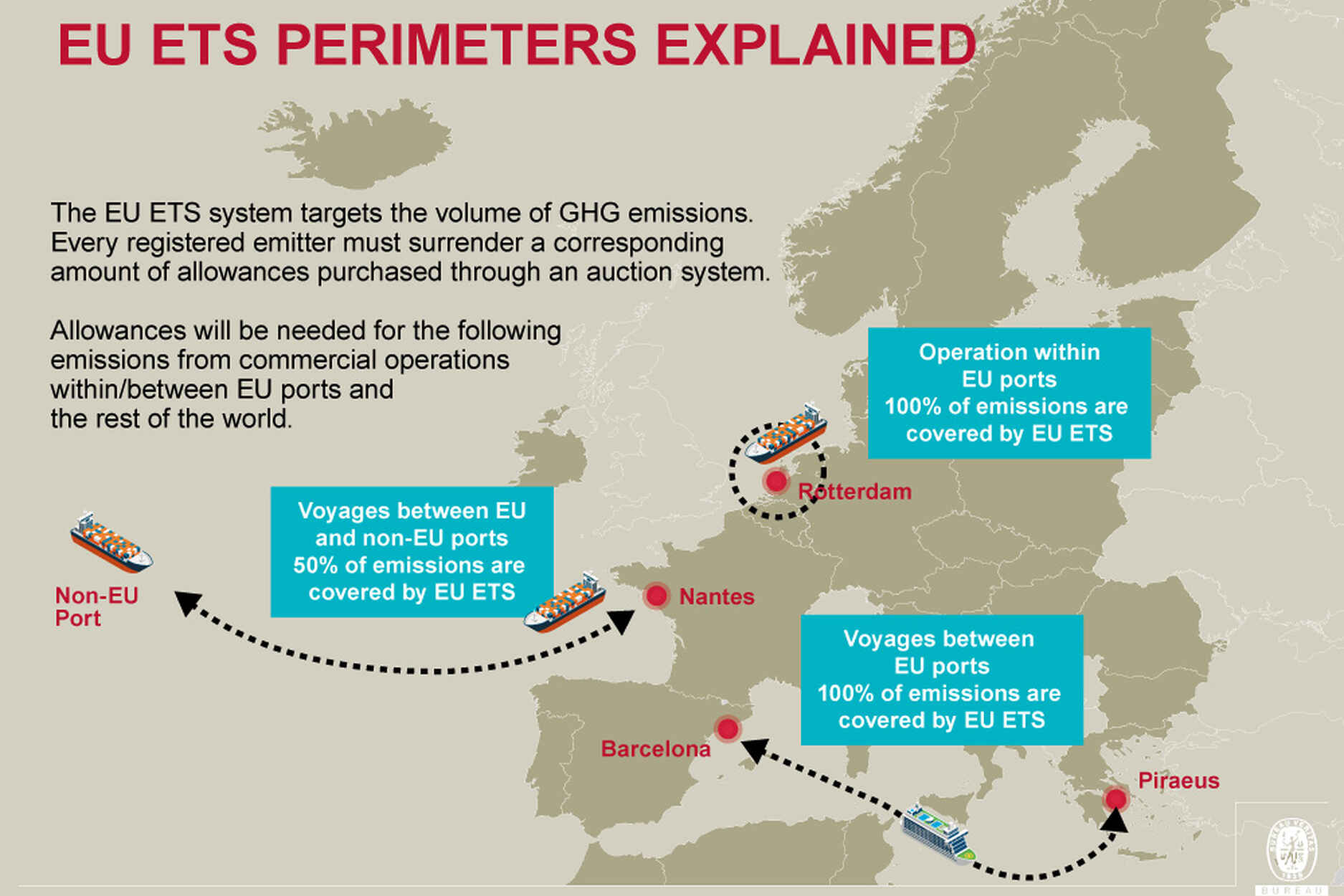

What does the system cover? The EU ETS covers 100% of the emissions that occur between two EU ports and when ships are within EU ports, and 50% of emissions from voyages starting or ending outside of the EU (allowing the third country to decide on appropriate action for the remaining share of emissions) (Figure 2). In detail it covers CO2 (carbon dioxide), CH4 (methane), and N2O (nitrous oxide) emissions, but the two latter only as from 2026.[10] To give enough phasing-in time for the companies regarding registering their emissions, preparing their inventories, accounting systems, etc. the Commission proposed that shipping companies will have to surrender allowances for a portion of their emissions during a phase-in divided into three periods:

1. 2025: for 40% of their emissions reported in 2024;

2. 2026: for 70% of their emissions reported in 2025;

3. 2027 onwards: for 100% of their reported emissions.[11]

Figure 2 - EU ETS for maritime and its boundaries

After 2026 full compliance is mandatory. All emissions from maritime transport are going to be included in the overall ETS cap, which defines the maximum amount of greenhouse gases (GHG) that can be emitted under the system. The cap is reduced over time for all ETS sectors, to incentivize the industries that emit a lot to contribute to the EU’s climate objectives[12] The inclusion of the entire EU maritime transport and 50% of the shipping between EU and non-EU regions is a clear sign that the GHG emitted need to be paid, and that companies that decarbonize faster will have lower costs down the line. This will further incentivize the closing of the price gap between the still quite expensive alternative green fuels and the traditional maritime fuels like diesel and LNG.

EUFuel Maritime

Another important legislation coming out of the EU regarding lowering emissions and pushing for fuel switches in the shipping industry is the so-called EUFuel Maritime. The legislation is focusing on lowering the greenhouse gas intensity of fuels used by the shipping sector, starting with a decrease of -2% in 2025, getting at -6% om 2030, and gradually increasing to -80% of less GHG intensity of the fuels used for shipping by 2050. The end goal of the measure is to promote the usage of clean fuels and energy in shipping. Why is there a necessity for a push to not only lower emissions but to target the fuels used as well? Maritime transport is a highly competitive industry, where long-term purchasing contracts are not the norm for the energy used, since short-term wise the cheap fossil fuels they are using are a) available b) allowed. To push the operators and owners of the vessels towards the more expensive alternatives there needs to be an ’incentive’ from the regulatory bodies with a ‘stick’ policy - stricter targets and penalties if those targets are not reached, and a ‘carrot’ policy - financial support offered for those who will be early movers. The point of EUFuel Maritime is precisely to penalize those who are reluctant to do the fuel switch and reward the planning first movers who will at the beginning risk by choosing scarce and costly e-fuels. Therefore, the FuelEU Maritime regulation will impact shipping in EU waters not only in terms of fuel choices in the long term, but in operational costs in the short- to mid-term[13], even if operators and owners of the vessel think that reaching -6% reduction target in less than seven years as of today would not be a problem.

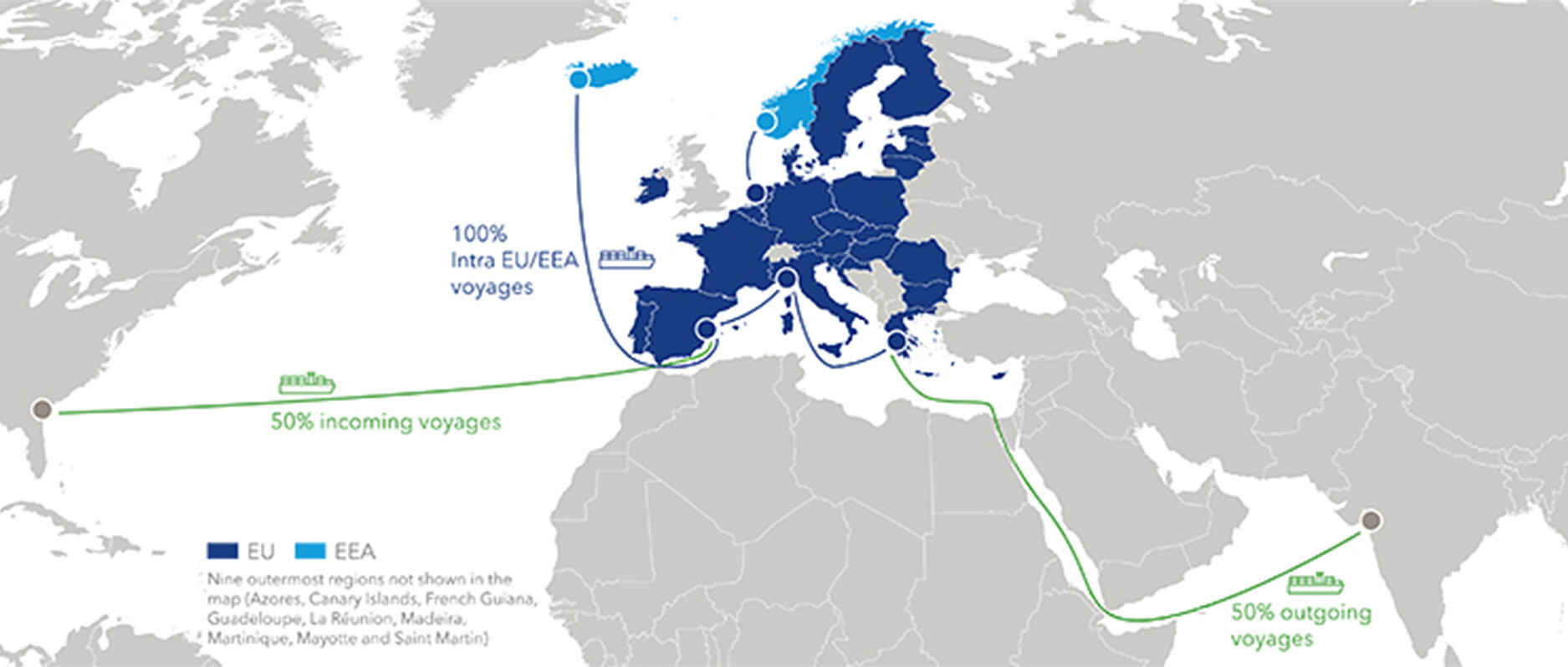

What does EUFuel Maritime entail apart from the GHG reduction targets? Similar to the EU ETS, its scope encompasses 100% of EU shipping and 50% of the outgoing voyages, but with the added EEA members Norway and Iceland, (Figure 3). For vessels to not find a loophole in the regulation, the EUFuel Maritime has an additional clause, stipulating that container ships stopping in transshipment ports outside the EU or EEA, but less than 300 nautical miles from an EU or EEA port, need to include 50% of the energy for the voyage to that port as well, rather than only the short leg from the transshipment port to the EU waters. Which transshipment ports will be included will also be instructed by the EU authorities. All CO2-eq (CO2, CH4, N2O) are part of the scope of the regulation, same as in the EU ETS, including emissions related to extraction, cultivation, production, and transportation of the fuel, in addition to emissions from energy used on board the ship. These emissions are calculated from a well-to-wake perspective. Further, there is an obligation for passenger ships and containers to use the on-shore power supply for all electricity needs while moored at the quayside in major EU ports as of 2030, to mitigate air pollution in ports, which are often close to densely populated areas.[14]

Figure 3 - FuelEU Maritime requirements based on the percentage of energy used on voyages

This regulation also has measures to encourage the use of the RFNBO and it is excluding fossil fuels from the certification process of the allowed fuels by improving the provision to make the process more future-proof. As LNG at the moment is a cheaper option than e-fuels and a less polluting alternative than diesel, many operators might believe that switching to LNG would be enough for compliance under the new regulation. Such maneuvers however will be hard as EUFuel Maritime looks at the fuel itself rather than focusing only on the emissions reductions. Hence exposure to FuelEU Maritime penalties can only be reduced significantly by changing fuel technologies.

Revenues generated from the penalties of those vessels which will not be able to stay within the reduction targets will most likely be allocated to projects to support decarbonization of the maritime sector with an enhanced transparency mechanism (so if a company wants to avoid a penalty and get funding for its further decarbonization this will be a good time to decide on that). FuelEU Maritime effectively rewards ambitious adopters by decreasing the surplus (what the company can get as allocation from the penalties others pay) for over-achieving compliance over time, while multiplying the penalty for failing to meet the targets[15]. Hence, the sooner the operators and/or owners of the vessels switch the better.

EU Fuel Maritime is also an opportunity to offset an entire fleet or pool’s penalties with just a few over-performing vessels. There is a voluntary pooling mechanism, under which ships will be allowed to pool their compliance balance with one or more other ships, with the pool – as a whole - having to meet the greenhouse gas intensity limits on average.[16] An example would be a cargo company operating 100% within the EU procuring one ship in its fleet that runs on e-methanol, which depending on the full fleet it owns/operates can in theory over-shoot the -6% reduction target for 2030. Therefore, it has an incentive to offer a voluntary pooling agreement to other vessels, for a certain price (their emissions would have to be verified by the same verifier). Such an option can be seen as an additional incentive to early movers to procure or re-furbish partly their fleet to be able to use e-fuels which is expensive but can be covered by these additional revenues. This part of the legislation would need further clearance by the time it is in full force in 2025, as it is not clear which company or vessels under such a pooling arrangement would get the revenues in case of over-compliance, is it the company owning the vessel that is running on e-fuels or the operator under which that vessel sails. All in all, EUFuel Maritime might just prove to be the right incentive for the shipping industry to finally start putting in place concrete measures for its decarbonization.

Why e-methanol for ships?

The above-described regulations make it clear that it will be increasingly difficult for companies to claim to switch to natural gas/LNG in them reducing emissions as natural gas is still a fossil fuel and its GHG intensity is much higher than that of e-fuels. Just as an example, according to the Canadian Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources, LNG has an intensity of 112.65 gCO2e/MJ[17], while in the EU e-fuels or RFNBO need to lower their emissions by min 70% compared to the fossil fuel comparator which is set at 94g CO2e/MJ[18]. So even if suppliers can claim emitting less CO2-eq due to the switch from diesel engines to LNG overall, the GHG intensity reduction targets by the FuelEU Maritime would require more efforts as they will be looking into the characteristics of the fuels themselves, with additional targets for clean fuels and CO2 price on each emitted CO2 on top of that.

Therefore, apart from implementing necessary energy efficiency measures the long-term goal is obvious: a full switch to clean fuels. It is understandable that in the short to medium term, companies cannot replace their entire fleets that run on fossil fuels. This is a gradual process that should take into account the changes and development in fuel and engine technologies.[19] Gradual replacement also makes economic and environmental sense due to the materials needed to build the vessels. In such circumstances, the next logical step would be to look into refurbishment and gradual addition to the fleet of vessels that run on e-fuels as the ramp-up of clean fuel production increases simultaneously. In this regard several points are important to keep in mind when deciding what e-fuel to use, the amount of renewable generation capacity necessary (as it will be significant), the adequate land availability for the production of solar or wind as space and renewable conditions vary greatly from place to place, the additional feedstock needed such as biogenic CO2, and the suitable governance and policy environment to support the industry, as e-fuels produced elsewhere but sold to EU market would need to adhere to the strict EU regulation.

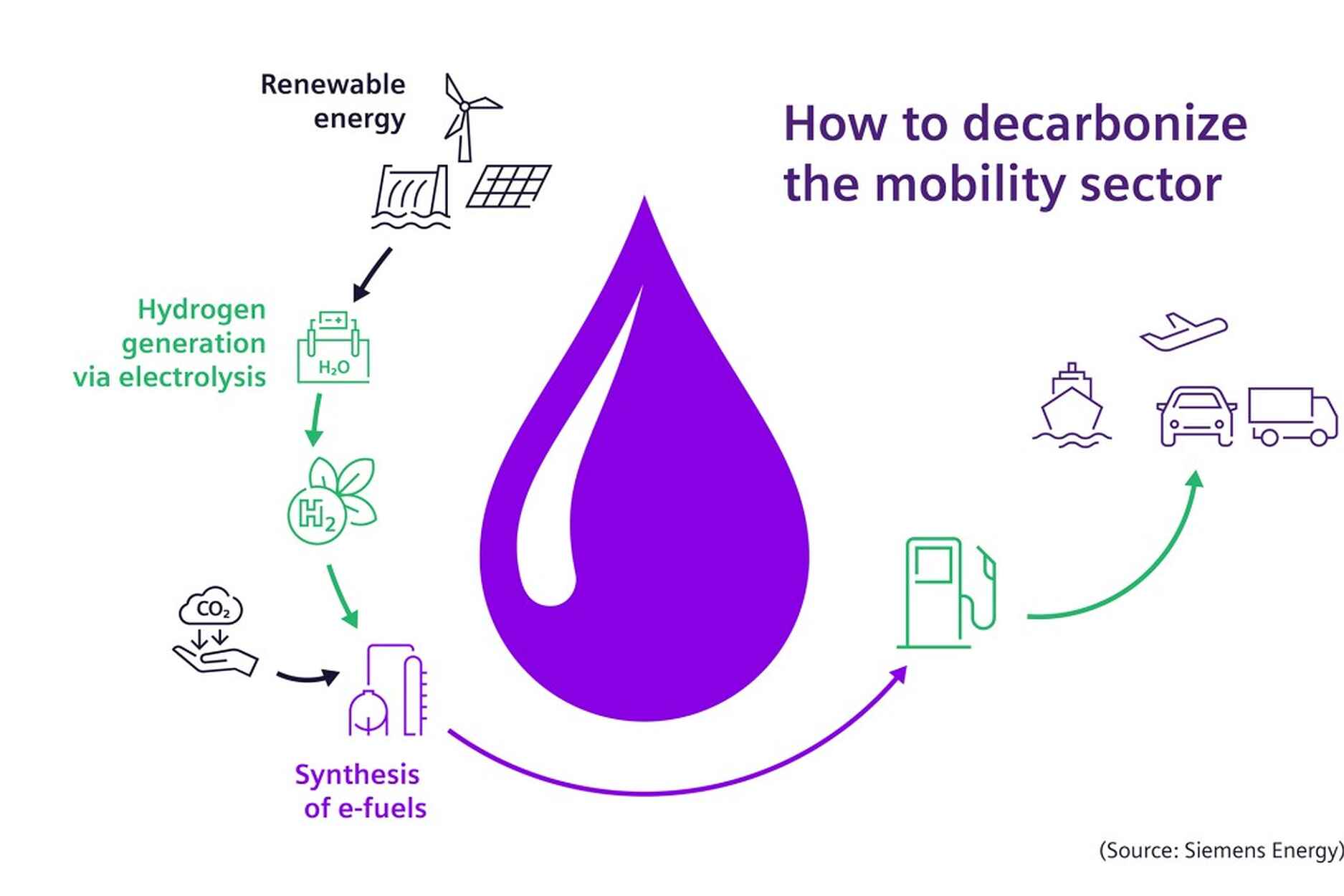

How can e-methanol support the decarbonization of shipping? Several fuels are being taken into account for shipping decarbonization, one of them is e-methanol due to the many advantages it can have when compared to other maritime fuels. Methanol is already produced in large quantities (granted at the moment it is entirely brown or gray methanol from fossil fuels while green methanol is less than 0.2 Mt of the production annually, mostly defined as bio-methanol[20]), it is easy to handle, and combust, and safe to use it onboard, as there are well-established rules and regulations about it as a marine fuel in the form of the IMO’s MSC.1-Circ.1621 – Interim Guidelines For The Safety Of Ships Using Methyl/Ethyl Alcohol As Fuel.[21] If strictly following the Delegated Acts (solar/wind for the hydrogen plus biogenic CO2) (Figure 4), it can offer significant reductions in GHG and air pollutant emissions compared to the other fuels currently in use in shipping (LNG; Diesel, etc). Its GHG intensity can vary between 0.5-33 CO2eq/MJ, whereas grey methanol is at ca 95 g CO2eq/MJ.[22]E-methanol is made by combining green hydrogen with carbon dioxide, and is liquid at ambient temperatures and pressures, and therefore holds more energy in less space than natural gas. That makes it more efficient to transport and store.[23]

Figure 4 – E-fuels pathway

This leads to the point that e-methanol can be used immediately, i.e., in the short term where the first targets set by the new EU regulation (as of 2025) will need to be fulfilled by the companies. Further, methanol has the advantage that it is similar to traditional fuels. It is a hydrocarbon and a liquid. This makes it easier to allow dual-fuel engines that can run traditional fuels or methanol[24] especially since e-methanol has not hit the market yet. That makes the cost to build new vessels and retrofit existing ones to run on methanol significantly lower than for alternative zero-carbon fuels which would require new engines and vessels. Also, unlike ammonia liquid methanol does not need to be stored under pressure or at extremely cold temperatures, is far less toxic to handle, and has fewer pollution issues.[25]

Hence, while the technology is developing and we are waiting for greater electrification of shipping or batteries that can replace engines, e-methanol will have an important role to play in decarbonizing the main transport of goods in our economies. However, for rapid scale-up of this clean fuel the cost of its production would need to be less than what are the current estimates in the literature. According to IRENA, the cost of e-methanol is estimated to be in the range of USD 800-1600/t assuming CO2 is sourced from BECCS (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage). If CO2 is obtained by DAC (direct air capture)…then e-methanol production costs would be in the range of USD 1200-2400/t.[26] Regarding grey methanol, the literature puts state-of-the-art methanol production from natural gas as low as EUR 268.5/ton, while an advanced plant using gas switching reforming attains a cost of EUR 252.2/ton.[27] The significant difference in the cost of production of methanol depending on the feedstock (fossil fuels vs. renewables) showcases how important it is to enable a vibrant market for e-fuels, with targeted governmental support in guaranteeing the off-taking up to a certain price where the demand will be ramped up and met fully on the market, and clear regulatory environment by having targets for not only emissions reduction but also usage of clean fuels in hard-to-electrify sectors like maritime. Furthermore, the estimations are that e-methanol is likely to be more expensive than other fuels like ammonia due to the cost of the feedstock (renewable power, CO2) in the decades ahead, necessitating a significant upscaling of its production to meet the fuel demand of shipping.[28] It is also clear that there is no abundant biogenic CO2 to be harvested for the production of e-methanol, as especially in the EU biomass/biogas production will most probably have limited application[29] in a decarbonized system. This is not necessarily a bad outcome considering the need to have crops and forests protected as we experience climate change effects with more severity, however, it is important in a circular economy to utilize all aspects of production, hence having clear targets for RFNBO, including e-methanol helps the full utilization of CO2 that is byproduct of biomass combustion.

In the end, by 2030 as a key target year when the EU will assess whether it is on the right track to decarbonize, the share in the clean fuel mix of the different e-fuels will be determined by several factors: upscaling of e-methanol production, decrease in fuel cost, and acceptance of ammonia in the maritime sector.[30] There are several large projects in the making ready to start delivering e-methanol in the next 3 years, galvanizing the usage of fuels that were unthinkable a few years ago. A sector like maritime, responsible for 5% of global fossil fuel consumption can see its rebirth in less than a decade with new fuels, which harvest the wind and sun instead of the oil and gas. Clear targets, funding, and off-take under a level playing field rules will be of the utmost importance to see this vision turn into reality. What we need now is pioneers and first movers in both supply and demand as well as in decision-making.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions or views of Green Enesys or any of its affiliates or partners.